It’s easy to get misty-eyed about voting. But it is just as important to be clear-eyed about our systems’ strengths and weaknesses and how they can be improved to ensure participation among Arizonans.

By Nancy Welch

Arizona Center for Civic Leadership

The 2020 election cycle is well underway, and participation is expected to be high, given current events and the 2018 experience. Not since 1982 has midterm election turnout in Arizona been as high as it was in November 2018. The stronger-than-usual participation has been attributed mainly to post-2016 energy, a hotly contested U.S. Senate race, responses to such state and national events as #RedforEd and school shootings, and effective GOTV (get out the vote), especially among young people, women, and Latinx.

To support involvement among the approximately 4.9 million “voting eligible” Arizonans and take some of the mystery out of election administration, Voting in Arizona: Choices, Mechanics, and Competition provides basics on who’s who, patterns, and issues—plus how to get involved at the polls.

Even though turnout in the millions sounds impressive, some 1.3 million registered Arizonans did not participate. Roughly another million could have registered and did not. Clearly, Arizona has a lot of room for improvement.

The Civic Participation Progress Meter from the Center for the Future of Arizona puts a fine point on the issues. The progress meter tracks the status of voting as one of seven measures of civic health in Arizona and the nation. These measures give policymakers, residents, and activities a scorecard to help improve the state’s performance.

Change is the norm over time

The U.S. history of voting and elections has been one of moving from exclusive to inclusive, voice votes to secret ballots, monolithic parties to many players, and acceptance of discrimination to working to eliminate it. The idealized notion of the “informed voter” emerged as a norm in recent decades, even as the concept of citizenship, as opposed to residents as consumers, seemed to decline. Now the fragmentation of communities and media, a decrease in trust of government, campaign-finance changes, polarization, and legacies of discrimination are some of the causes of a negative environment for elections, although many institutions are working to mute the effects of recent trends. Leaders have designated election systems themselves as “critical infrastructure,” but tension between competing visions for participation and political interests remains high, while technical and cultural threats increase, and involvement is lackluster. Voting still calls to mind individual acts, but it is only public systems that can make every vote count.

Voting practices vary widely

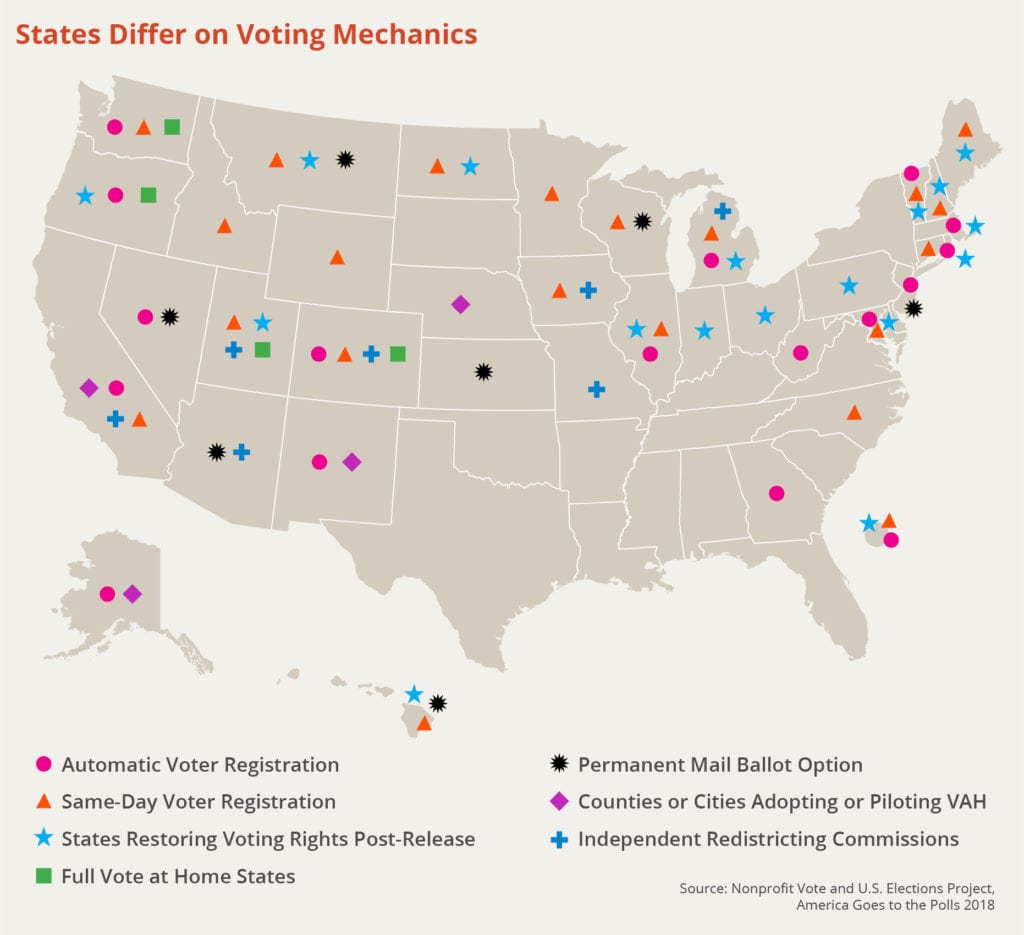

Voting experiences and mechanics throughout the U.S. are far from simple, static, or uniform. The federal government, states, counties, municipalities, and civic organizations play various parts in numerous types of elections, especially with the rise of real, and imagined, concerns about access and security. Ballot initiatives, administrative choices, court decisions, and legislation over decades have produced a decentralized public/private complex that differs from state to state.

For example, Arizona has online voter registration, early voting, a Permanent Early Voting List for mail-in ballots, and no-excuse absentee voting. However, due to a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Arizona also has a unique “bifurcated” voter-registration system that requires voters to prove citizenship in order to vote in state and local elections but has no such requirement for voting in federal elections.

Those on the front lines of election administration and voter engagement must navigate a host of rules and policies to ensure compliance, fairness, and access. In Arizona, major players in election administration include:

Secretary of State

The elected secretary of state (SOS), among many other duties, serves as Arizona’s chief elections officer. The election role includes many responsibilities. For example, the SOS oversees election policies and procedures for counties and municipalities, campaign finance for statewide and legislative candidates, verification of initiatives and referenda, and certification of election results. The SOS also plans for, receives, and distributes federal funds for such resources as new voting equipment, as was provided by the national Help America Vote Act (HAVA) in 2002.

Arizonans can register and voters can track their ballots through the SOS’s office, too. In addition, the SOS maintains a federally required single voter registration list and updates it nightly with data from counties. Voting machines are tested prior to every election. Allegations of campaign-finance violations are reviewed in conjunction with the attorney general. Historical data on registration and turnout are also available.

County recorders and county boards of supervisors

Throughout Arizona, county recorders tend to be the “faces” of elections, but county supervisors also have critical functions, since state statutes divide responsibilities between the two elected offices. Recorders oversee voter registration and, generally, the documentation of voting, including early-voting records, while supervisors, usually through directors, tend to equipment, staff, and polling operations. Some county boards (including Maricopa County until recent changes), assign nearly all election duties to the recorder. Other county boards, such as Pima and Pinal, have appointed elections directors who work closely with the recorders. Recently, the Yuma County Board of Supervisors delegated elections duties to the Yuma County Recorder’s Office, which then hired an elections director.

Citizens Clean Elections Commission

Voters passed the Arizona Citizens Clean Elections Act in 1998 to establish public funding and matching programs for candidates for state-level offices and voter education, plus oversight of campaign finances and independent expenditures. Clean Elections is administered by a nonpartisan commission and derives its funds mostly from a 10 percent surcharge on civil penalties and criminal fines. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down the matching-funds formula in 2011.

Since that decision, candidates may still use public financing, but the dollars are substantially less, even after inflation adjustments. Many candidates now choose to raise funds traditionally, rather than use Clean Elections. The Act also requires Clean Elections to deliver a voter-education guide to every household with an Arizona registered voter. This results in roughly 1.8 million guides being delivered for every statewide election. Additional voter-education information can be obtained at the Clean Elections website.

Civic, service, and political organizations

Scores of private, nonprofit and social-welfare entities engage Arizonans in all facets of campaigning, voting, and election implementation. For example, One Arizona is a coalition of 17 organizations involved in the gamut of voting activities. LUCHA (Living United for Change in Arizona) and Mi Familia Vota are active statewide, also. The Republican and Democratic parties are also players in registration and voter turnout, among many campaign-related activities. School and community-based civic education to develop voting habits among youth has been revitalized recently, too. Inspire U.S. and Tomorrow We Vote Action, for example, work with Arizona high-school students to ensure they understand the importance of voting and follow through on registering.

Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (IRC)

Voter participation at every level is always affected by who is running and what is on the ballot, which, in turn, are influenced by the makeup of districts. Boundaries for Arizona’s congressional and legislative districts are now drawn by a five-member bipartisan Independent Redistricting Commission (IRC), instead of by the legislature, due to a voter-approved ballot measure in 2000. Commission members are appointed by the speaker of the house and president of the senate after each decennial census. Appointments for the next IRC are expected by January 2021. Working with new counts from the 2020 Census and public input, these leaders will create boundaries so that legislative and congressional districts include an almost-equal number of residents, as required by the Arizona and United States Constitutions. Many other bodies will use the same data to draw other types of lines.

In addition, the Arizona Constitution notes that districts must be “geographically compact and contiguous” and “respect communities of interest,” following “visible geographic features, city, town, and county boundaries, and undivided census tracts,” all “to the extent practicable.” The constitution favors making districts competitive “where to do so would create no significant detriment to the other goals.” Redistricting is a contentious process, since it has big implications for future elections.

Selected Arizona Voting and Elections Milestones

Over the years, Arizona and federal officials have made many choices that affect participation. Some have been shown to facilitate participation and turnout, while others impose burdens that reduce it.

| 1912 » | Arizona Statehood. Women’s suffrage approved by initiative. |

| 1948 » | Harrison v. Laveen, Native Americans win right to vote in Arizona. |

| 1975 » | Arizona becomes “covered” under the 1965 Voting Rights Act and subject to “preclearance” to remedy and prevent discrimination. (SCOTUS Shelby v. Holder ends preclearance.) |

| 1982 » | Arizona Voter Registration by Driver’s License passed by voters. |

| 1998 » | Arizona Voting in Primary Elections passed by voters, allowing “independents” to vote in primary elections. |

| 1998 » | Voter Protection Act passage limiting changes to voter-approved measures passed by voters. |

| 2000 » | Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission approved by voters, first U.S. state to do so. |

| 2004 » | Voter ID and proof-of-citizenship requirements passed by voters. |

| 2007 » | Permanent Early Voting List established by legislation. |

| 2011 » | SCOTUS Arizona Free Enterprise Club v. Bennett strikes down Clean Elections matching-funds formula. |

| 2016 » | Prohibition on collection of early ballots by others, except family members primarily, approved by legislature. |

| 2018 » | Primary election date moved to first Tuesday in August from last Tuesday in August by legislature. |

Arizona’s shifting participation patterns

Despite residents telling researchers that voting is important, Arizona has long lagged among states on voter participation, although it has been a leader in redistricting and some aspects of elections. Some observers have blamed Arizona’s rapid growth for a weak civic culture. Others point to outdated rules and participation requirements, such as early pre-election registration deadlines, identification requirements at the polls, and late-summer primaries as causes. Not surprisingly, increasing participation has been a popular goal among policymakers, civic leaders, and activists and a motivation behind such measures as early voting and “motor voter” registration.

Studies show that Arizonans, and Americans, vote often because of personal responsibility, habit, community norms, peer expectations, self-expression, and a desire to belong. For those for whom voting is a sacred duty or simply a long-term habit, it is hard to fathom why many don’t participate. But there are reasons. Notable concerns that nonvoting citizens disclose include too-little time, their votes not counting, illness or disability, conflicting schedules, complexity, and dissatisfaction with candidates and politics. Voter experience matters, too. For example, long lines and confusion about polling places (as in 2016 and 2018 in Maricopa County) may turn off participants for future elections.

Research reveals that such processes as vote by mail, same-day registration, and automatic registration can improve voter participation by providing more time and flexibility. However, smooth elections, regardless of form, depend on a combination of often byzantine processes all going according to plan.

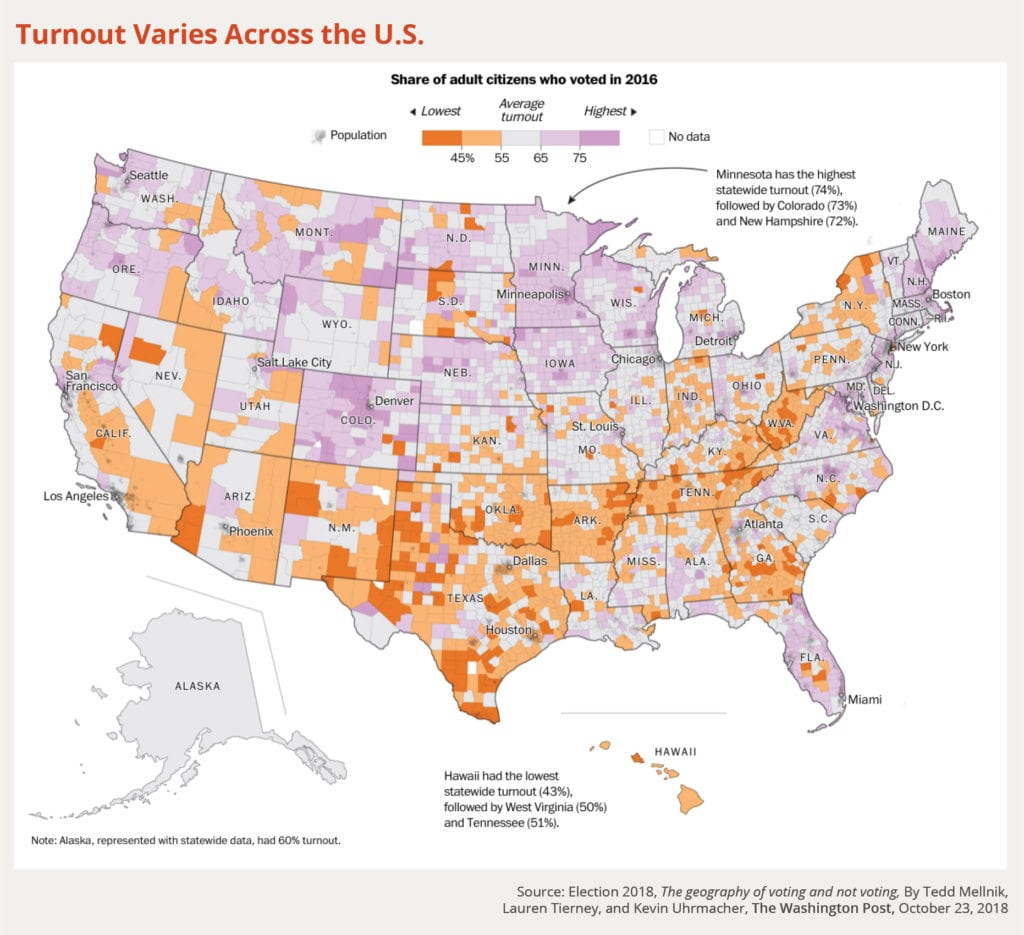

Different definitions for the electorate make voting results confusing, too. For example, the “voting-age population” (VAP) includes everyone in the state 18 years of age and older. The “voting-eligible population” (VEP) refers to those 18 and older who can vote, meaning chiefly that they are U.S. citizens. “Registered voters” have signed up officially and maintain their status as they move within the state. For example, in 2018, Arizona’s turnout among registered voters was 65 percent. That was 49 percent of the voting-eligible population, however, putting Arizona 33rd in the nation. Especially in redistricting work, “citizen voting-age population” (CVAP) is frequently cited along with VEP.

Election officials record who has voted and the personal data reported at registration, but they do not know how individuals mark their ballots. Thus, each data source about voters—from the U.S. Census to official state elections offices to interest groups and researchers—reports in different ways and often relies on self-reporting. Patterns, as a result, tend to be consistent across different definitions and sources, rather than showing the same exact numbers.

Researchers, campaigners, and pollsters increasingly use “voter files” to study participation and model future turnout. Voter files start with official voter registration lists. These files then are supplemented with data, often purchased from compilers using many public sources and private research, on whether individuals voted in previous elections, how, and why.

The importance of data is as evident in voting as it is in today’s consumer contexts. Also, mobile technology has become integral to participation and campaigns, with widespread use of tools such as OutVote and RumbleUp. Fine-grained information from many sources drives analyses among those wanting to increase participation, design campaign strategies, and understand civic health.

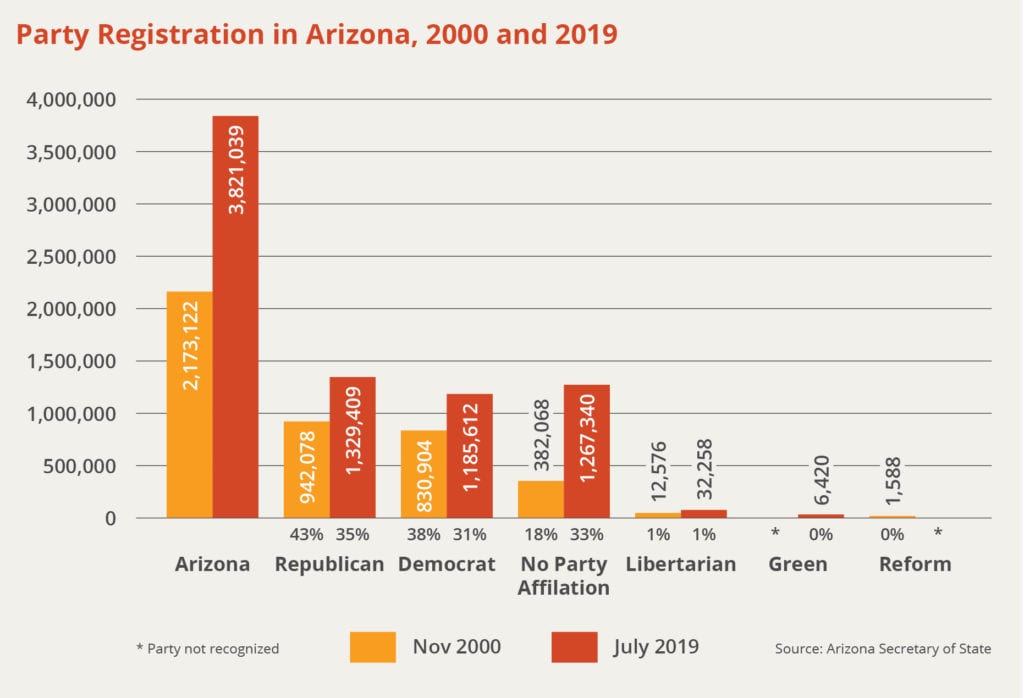

More Arizonans don’t identify with a political party

Nearly all Arizonans used to register as Republicans or Democrats or as members of smaller parties. Now, “no party affiliation” (NPA) is common. “Unaffiliated” voters are often characterized as “independents.” However, research has shown that most NPA voters lean toward one major party or the other.

Participation lags in primaries and midterms in comparison to presidential years

Midterms generally have lower turnout than presidential years, although 2018 approached the presidential participation level. Candidates, election administrators, and campaign operatives are trying to determine now if 2018 is a new normal or an outlier.

Many more minority voters are turning out

Arizona’s minority populations’ participation has lagged white turnout traditionally, although African American women continue to be leaders in turnout in Arizona and the U.S. The minority pattern is shifting nationally and in Arizona, especially among the Latinx (the state’s largest minority population) and Asian-American communities. Arizona is now fifth among states with 1,145,000 eligible Latinx voters. With a young population increasingly of voting age, and mobilization energy, the Latinx community is coming into its own. From 2014 (an election with low turnout even by midterm standards) to 2018, participation in Arizona among registered Latinx approximately doubled, according to research by Univision, and young voters accounted for much of the change. Early voting also increased dramatically. Estimates reported by Univision point toward double-digit growth in 2020 for Latinx.

Age, income, and education have combined for influence

Younger voters have historically ceded political clout to their elders, who for years have turned out in the highest numbers. However, youth participation has been inching up for years and grew significantly in 2018. Data calculated by the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement showed an increase in youth turnout of 16 percentage points in Arizona. “The total share of votes cast by youth nearly doubled, demonstrating an increase in young people’s influence on the election.” But age is only one factor in voting patterns. Those with higher incomes and more education also participate at higher rates. Substantial work is in progress to bring MIV (missing in voting) Arizonans into the process.

For example, since eligible 18-29 year-olds have represented the smallest group of registered voters in Arizona in recent elections, the Citizens Clean Elections Commission’s Take Flight initiative: “18 in 2018” targeted young people for the midterm election.

The Commission created a building mural linked to the Shazam augmented-reality platform as well as a special webpage and used the power of video and social media to allow new voters, especially those turning 18, to register and share their experiences via a secure smartphone app. The Commission’s work increased youth turnout significantly and earned a prestigious national PRWeek Award in the “Best in Public Sector” category.

Women now outnumber men at the polls

Arizona recognized women’s right to vote in 1912 and the U.S. followed that lead in 1920. For decades, however, women lagged men in turnout. That has changed in recent elections, with women now outpacing men in Arizona and the nation. The U.S. Census Bureau reported that women continued to vote more than men in 2018, “just as they have in every midterm election since 1998.”

Arizona’s voting future

What now for Arizona? Will the MIV numbers go down? Will participation rise? As everything does in elections, it depends on many factors.

Will Arizonans work together to reduce MIV and increase participation overall?

More Arizonans are now born in the state, and thus may have deeper roots and greater civic devotion. Civic education is making a comeback, while hundreds of entities are finding new ways to register and engage voters. Momentum is also gathering behind mechanisms such as automatic voter registration and same-day registration that have been discussed in Arizona for some time and adopted in a variety of states. If new mechanisms lead to more and more young and Latinx voters, election profiles could change dramatically.

Will we ensure access especially?

Many observers and some recent reports point to reductions in the number of polling places, laws against collecting early ballots, and other activities as “voter suppression” techniques that disproportionately affect minority communities, low-income voters, and rural areas. With Arizona no longer covered by “preclearance” as part of the federal Voting Rights Act, the possibility for reducing access to the polls is viewed as being a greater risk than since the 1960s. However, initiatives such as voting centers, which have been introduced in the most recent elections, may also have a positive effect.

How will new district boundaries affect candidates and competition in elections?

Arizona is again one of the fastest-growing states in the nation. The 2020 Census is expected to award the state another Congressional seat. As new boundaries are drawn for state-level and Congressional districts, more candidates may see new opportunities, while traditional outcomes may be challenged by greater competition. The Latinx community’s gains may well play a leading role, as will numerous other demographic changes.

Will new tech systems work and still be easy and secure?

“I can bank on my phone. Why can’t I use it to vote?” The reality is that voting is more complex in some ways than even financial services. Plus, administrators must deal with old equipment and insufficient resources to replace machines or create secure innovations. The threat of election hacking is only expected to grow, even though the decentralization of state and local systems offers a safeguard. Elections administrators will have to get any changes right the first time to meet the electorate’s expectations and avert bad-actor incursions. Even so, real improvements are possible.

It’s easy to get misty-eyed about voting, because it is central to governance and many Americans’ views of themselves. But it is just as important to be clear-eyed about the strengths and weaknesses of our systems, and what will enable us to build on the successes of the past, address failings from yesteryear, and prevent new problems. Arizonans’ behavior and attitudes will make as much difference as voting tech and policies. The individual choices and public systems are closely intertwined.